So, I’m a level 5 Goliath Barbarian. I wield a magic Great Axe named Soul Nommer. My spirit animal is a ‘Capybeara’ called Epictetus. He’s a hybrid Grizzly Bear/Capybara. Obviously.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Design and Development in the realm of Tabletop Games. Dungeons and Dragons, the Grimdark world of Warhammer 40k, family favourites; you know, Monopoly, Scrabble, Connect 4. Fond memories indeed. Modern classics include Exploding Kittens, a Kickstarter record-breaker. Carcassone, and Ticket to Ride.

The modern tabletop industry is lucrative. As with most products. The best design triumphs: others are lost in obscurity, relegated to a dark corner of a local tabletop cafe basement. I personally enjoy that dark corner, assuming there are snacks.

“The global market value of board games, alternatively known as tabletop games, was estimated to be around 7.2 billion U.S. dollars in 2017 and was forecast to reach a value of 12 billion U.S. dollars by 2023.9 Aug 2019”

— Statista

Technology has enabled an enthusiastic hobbyist with the desire to create and publish a game independently. Kickstarter enables a designer to get their game out in front of an audience. Low-cost card printing services let them take it to market for a sensible price. Design in the tabletop space has been fairly democratised. It is no longer monopolised by monolithic publishers.

The design processes for tabletop games and digital products are analogous: Planning, prototyping, usability testing, product launch. So what factors make a great tabletop game? The experience: how does it play? Does a user feel delighted, or are they frustrated by the lack of instructions and clunkiness? A gaming experience should be compelling enough to repeat. Much like a user interface should be compelling so that a user will click to the next part of the application and make repeat visits.

Flavour: graphics and themes

Like a good User Interface, I’d expect legible typography and consistent iconography. As a player, I want to know what my card does, just by glancing at it. I can make better, faster decisions If the design language is clear and consistent. Colours should be accessible, language should be clear, of course — tabletop gaming is an inclusive activity.

Beyond the look and feel, graphic design brings a game to life. A game can have solid mechanics and be easy to learn. With that additional visual magic, that’s where a game can really shine through. Tone of voice and humour certainly add value too. Case in point: Exploding Kittens, the graphics are created by The Oatmeal, the comic site. They’re fun, quirky and playful… sometimes rude. Especially the NSFW version.

Remember Skeuomorphic Design? It never left the tabletop. Game designers want to match our tabletop system to the real world. Look at Ticket to Ride — imagine if it was a more minimal aesthetic. (Johnny Ives, look away now) , would it have the same character and deliver the same experience?

curse of the cat butt! a card with flavour

curse of the cat butt! a card with flavour

The Crunch: mechanics

In the end our game is a system. A program that initialises when the first player performs an action. That action changes the board state, or impacts on the next players action. Mechanics are tested, issues are debugged and refined through playtesting. Rules and specifications are produced.

Usability is key for good game mechanics. We want our users to focus on the game, not forced to constantly refer to the rules or the instruction manual, which distracts them from the overall experience. Is the recommended number of players 1–4? Add a fifth, it’s going to break the system.

World domination: just a few dice rolls away.

World domination: just a few dice rolls away.

Games Workshop: making users awesome

Games Workshop sell games, books, and plastic miniatures. In the age of VR, AR and Snapchat filters, they are a hugely successful money-making machine. What are they doing better than the competition? Making users awesome.

Rather than talking about the Chain-fist wielding superhuman characters of the 41st Millennium, I’m going focus on the experience that Games Workshop delivers…

When I walk into a store, I’m greeted by friendly, enthusiastic staff. Their passion and knowledge of the hobby are infectious. There are beautifully painted miniatures, dioramas, gaming tables. Everything is touchable, well-lit and pro-painted. The atmosphere is energetic, dice rolls herald shouts of victory as an opponent is engulfed in psychic fire.

Games workshop wants its users to be awesome. It has a hugely effective post user experience model. I buy a grey, unassembled plastic miniature, I am offered a free painting lesson and free gaming lesson. My grey lump of plastic comes alive in a flurry of (messy) colour and tabletop interaction. I see my ability immediately improve. I can’t wait to start my next project. Which means buying more miniatures. Ka-ching.

A Dreadnaught: This big robot dude just needs a lick of paint.

A Dreadnaught: This big robot dude just needs a lick of paint.

The good folks at Games Workshop want me to be great at the hobby. This is extended with their free Youtube tutorials and community content. I can learn pro-painting techniques. I have an online mentor sharing years of experience with me. I can watch battle reports to learn advanced gaming tactics.

“You have the chance to help people become more skilful, more knowledgeable, more capable”

— Kathy Sierra

The parallels between this model and the lessons from: ‘Badass: Making Users Awesome’ by Kathy Sierra are uncanny. (I encourage you to give it read)

Badass: Making Users Awesome’ by Kathy Sierra

Badass: Making Users Awesome’ by Kathy Sierra

Design tales from the dungeon

Questing straight to Dungeons and Dragons, or D’n’D. It’s that role-playing game the monster-prone kids from Stranger Things are into.

The questing party is composed of multidisciplined warriors each with a speciality. Does that sound like an Agile team, anyone? The quest is a collaborative experience design process. We work together to solve a problem, that problem often evolves at the whim of the Dungeon Master (DM). The party follow and expand upon the narrative; iterating and adding ideas. We respond to new requirements, which are usually more beasts to battle.

We roll dice, we fight Orcs and try our best to stay in character for an immersive gaming experience. Everyone’s experience is different and that adds a unique attachment to the game.

Building a team

Each session is a chance to explore a new part of the world set entirely in the theatre of the mind. There’s nothing visual, so communication is at the heart of a good quest. We discuss decisions before making them, and accept the outcome of a bad dice roll, usually with groans and painful consequences: read getting stabbed or burnt.

“If You Want To Go Fast, Go Alone. If You Want To Go Far, Go Together”

— African Proverb

Through collaborative storytelling, we build a great team that can communicate clearly and understand how to apply each others’ strengths to a particular challenge. We fail early and often, try out new ideas and don’t stifle the creativity of our fellow team members. Unless they happen to be seducing Necromancers during a battle.

Failure and documentation

As with any successful Agile project, we learn from failure regularly. As a Barbarian, dropkicking or headbutting a door is my preferred entrance to a new dungeon. It turns out, according to the party Storm Sorcerer —

“Doors can be opened, with the handle”

Who knew? After understanding this lesson in usability, I reserve my dropkicks for denizens of the dungeon.

— How not to learn from failure

We document the journey, logging events, encounters, and non-player character names. This documentation keeps everyone on the same page for the next sprint, sorry, quest. I suspect asking the bard to create a Confluence page wouldn’t go down well.

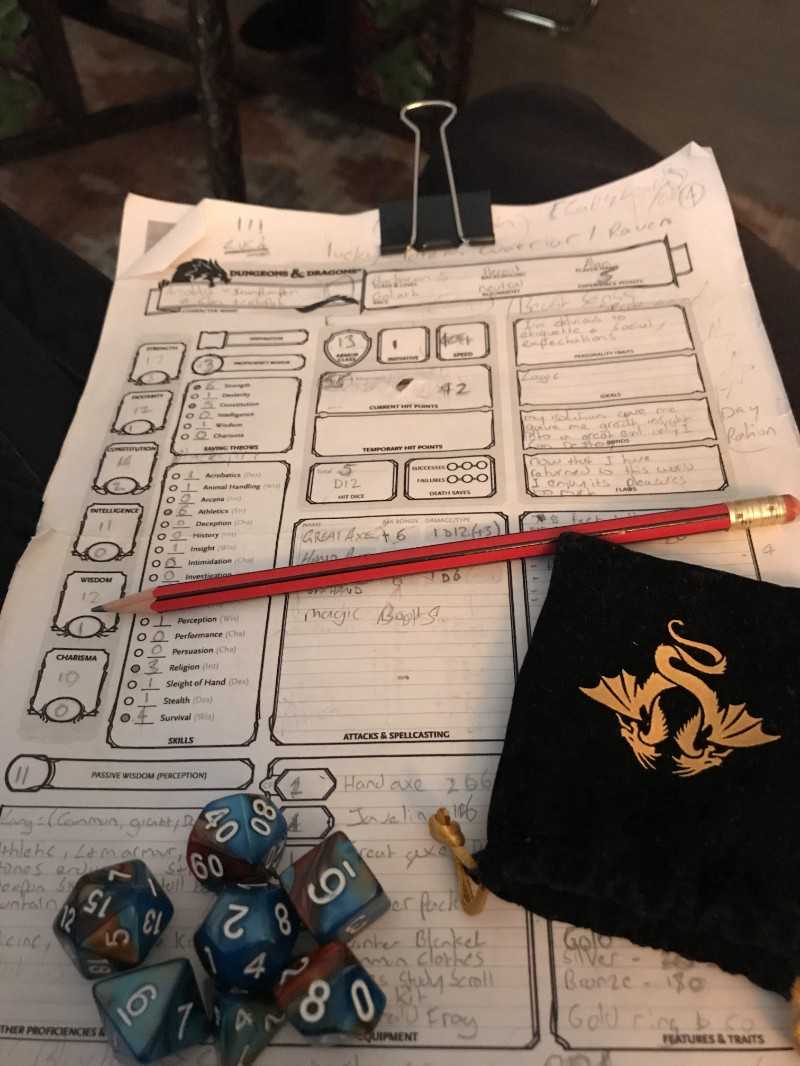

a well-maintained piece of gaming documentation. Pencil version control.

a well-maintained piece of gaming documentation. Pencil version control.

Things I’ve learnt from the tabletop

Designing an application or a commercial website? Here is my summary list of things I’ve learnt from the tabletop:

- Take inspiration from not so obvious domains.

- Help your users become awesome.

- Communicate and understand your team.

- Test and iterate, fail early and often.

- Dare to dream, and don’t go it alone — you’ll probably get murdered by feral Goblins.